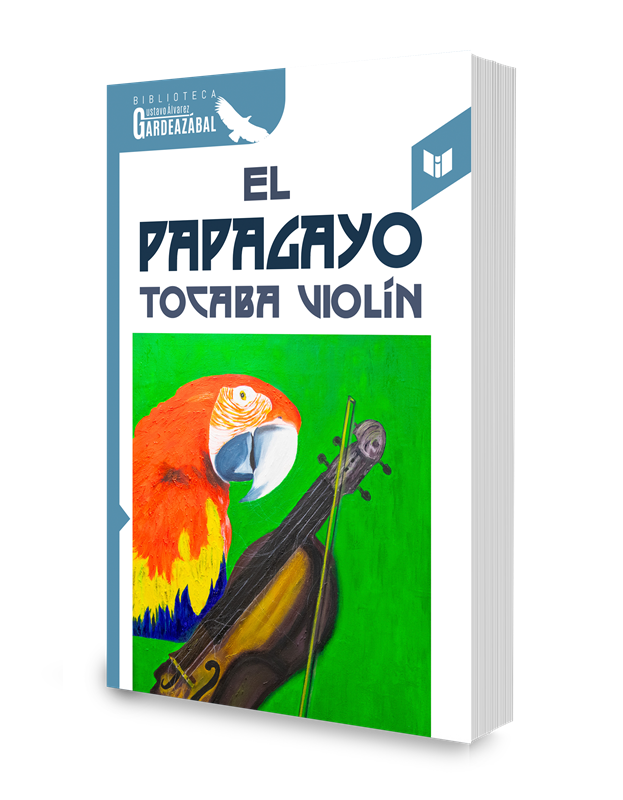

'The Parrot', by Gustavo Álvarez Gardeazabal / review by Cali writer Carmiña Navia Velasco

Gustavo Álvarez Gardeazabal has just presented us with a book that, he claims, concludes his literary career: "The Parrot Played the Violin," an excellent, hybrid and ambiguous text, somewhere between memoir, autobiography, and family saga. Reading it is an immense literary joy in multiple senses. Throughout these lines, I will refer to it as a novel for reasons of linguistic economy. Its structure is that of a novel, but it moves in a single line from the most unbridled imagination to the harshest reality.

The narrative journey begins with the birth of an I, whom we have no choice but to assume is the author's own. This newborn vomit-inducing child announces that he is going to record his life because his conscience allows him to, from the first moments of his birth. He then shows us a broad family environment in which, from the very first pages, two powerful figures emerge in the life and, of course, the personality of the "vomit-inducing": the mother, the bearer of violently rejected milk, and the maternal grandfather, the bearer of salvation for the baby-protagonist.

Readers await the development of this baby, but this story of the child being born moves through time and space, transporting us to vast worlds where we witness the construction of various cultures: those of Antioquia and the northern Cauca Valley, the mining and farming cultures of different lands, and some cities. But from here, we move much further, because in each of his works, Álvarez Gardeazabal updates Tolstoy's saying: "Paint your village and you will paint the world."

The narrative goes back at least four generations, and in it we witness the founding of towns and villages, national and local wars, family conflicts, heroic events, madness and suicides... all in a beautifully woven sequence that shapes the saga of two families united precisely in that "I," which, from beginning to end, becomes a clutch and release of time and space, of births and ruptures.

Gustavo Álvarez Gardeazabal's new novel, "The Parrot Played the Violin." Photo: Courtesy of Intermedio Editores

One of the novel's successes is the constant staging of the writing process itself . The narrator tells us how the idea for this story came about and how it was gradually constructed through his consultations in churches and notaries' offices, through his travels among his people, both present and past.

And precisely in this way, readers can access the narrative structure in which the author achieves his greatest and most original contributions and achievements. In this and other works, Gustavo Álvarez achieves a marvelous aestheticization of gossip. His stories—and not just this one—are constructed by recovering the resonant power of "word of mouth" and the sotto voce of people and of the human condition in general. The narrator winks at us in this sense:

He must not have been such a good soldier nor such a bad boss, because in the gossip that the Porce canyon became over the years, the battles of General Eusebio never became myths, nor were they talked about as much or in such detail as they still are about my grandfather Pablo and his gold-mining, sexual and alcoholic exploits.

I find it pertinent to transcribe the quote from the American journalist Francesca Peacock, in her essay: 'Gossip as a Literary Genre?': "It is worth using a practical definition. Like real-world gossip, literary gossip reveals truths that are normally hidden, the kind of information that is spoken about—when spoken about—in hushed voices. I use the term 'gossip' without its negative connotations: it is personal writing, whether about its author and their family or about other lives intimately known to them; it is writing that pushes the boundaries of what is acceptable to reveal, writing that is more (apparently) open, writing that leaves its author vulnerable on the page. Fundamentally, it is writing that has a reader in mind: the recipient of a letter, the recipient of a memoir, or even simply the author rereading their own diary. This conspiratorial nature seems to define the genre, regardless of the mass publication of a work; it is an affirmation of personal experience or secrets, combined with an awareness that these are will become (at least semi) public."

As we enter the Tuluá de Cóndores, or the town of Dabeiba, we witness the unveiling of information that has remained hidden or concealed but is essential to understanding the fate of the characters and the community itself. Sometimes we also wonder if we are witnessing real conspiracies... In the case of El Papagayo, what is gradually revealed to us are the intimacies of a family and the follies and successes of those through whom the story is constructed and transmitted: from the first suicide who hangs himself from a mango tree, to the rich great-grandmother who chooses a gay man as the father of her children, to the dedications and hobbies of the priest in the saga.

The entire novel is permeated by a fine and rich sense of humor , such that as we read it, we can imagine the mischievous smile on the face of the person writing the novel. This same humor is what allows parrots to play the violin or children just a few days old to record their memories. I have little left to say, only an invitation to read it. It is a work that caps off an enormously rich and varied literary journey.

eltiempo