The Wild West Treasure Hunt That Has Obsessed the World for More Than a Decade

What is more American than searching for buried treasure? That was the last text I sent to a friend of mine before my cell-phone reception dropped out in a desolate corner of Yellowstone National Park. It was 2013 and I was just a few months into reporting a story that would alternately fascinate me, frustrate me, and draw me back in again for more than a decade. Like many thousands of others around the world, I would become enthralled by the mystery of the Fenn Treasure and intrigued by the man behind it. Unlike most, I’d get to know him personally in the years ahead.

But all I knew that day was that I was worried about breaking an ankle, or worse, as I trekked through the vast wilderness of Yellowstone alongside a half dozen treasure-hunting obsessives I’d just met. My limited hiking experience hadn’t prepared me for what we faced, and my Nike sneakers were no match for the terrain. We slipped and slid off precarious rocks on remote mountain paths and climbed geothermal waterfalls in a region known to Yellowstoners as “the Firehole,” for the supervolcano some five miles below the surface. The current of the Firehole River was more unpredictable than our guides had told us, and the water much colder than you’d assume from the name. I managed to avoid serious injury, but we found no sign of the treasure. Coming back empty-handed was something I would get used to.

Searchers hunting for the treasure

Forrest Fenn himself had encouraged me to join the hunt. The octogenarian art dealer in Santa Fe wanted me to experience the thrill of treasure hunting firsthand so that I could understand why people from all walks of life had become so captivated—obsessed, really—with solving his riddles and being the one to get their hands on his buried loot.

In 2010, at the age of eighty, Fenn had self-published The Thrill of the Chase: A Memoir. In the book, he revealed that he had buried a bronze treasure chest loaded full of gold coins and nuggets, emeralds, diamonds, rubies, jade carvings, sapphires, and other precious objects. The value was estimated by others as between $1 million and $3 million, or more. (Fenn himself always refused to name numbers, maintaining that the price of gold fluctuates.) Hints about where the treasure was hidden were woven through the book, according to Fenn, and it included a poem that he said contained nine specific clues about the location of the chest. It was “in the mountains somewhere north of Santa Fe,” he wrote. Right there for the taking, if you could just crack the code.

It didn’t take long for Fenn’s vanity project to morph into a global phenomenon. A local legend in Santa Fe, Fenn had long rubbed elbows with and sold art to famous clientele like Ralph Lauren and Robert Redford. But the treasure made him a national celebrity in his own right. Newspapers and magazines flocked to the story. YouTube channels and blogs devoted to the hunt sprang up, and documentary filmmakers chronicled the story. Outside magazine called it “America’s last great treasure.” Many self-anointed experts published guides to the Fenn Treasure hunt. And Fenn himself became a regular on the Todayshow, periodically doling out cryptic new clues. “Fenners” from all over descended on the Rockies to hunt for the buried chest—several dying in the process.

Then, a decade into Fenn mania, came a pair of shocking events: First, in June 2020, during the height of the pandemic, Fenn posted on his blog that the treasure had been found. “So the search is over,” he wrote. He didn’t reveal the identity of the successful treasure hunter, but he subsequently released photos of the chest and in July revealed that it had been found in Wyoming. These developments sparked a variety of reactions from the legion of Fenn Treasure junkies: disappointment, disbelief, anger. This couldn’t really be the end. Was the treasure really found? Was it ever out there at all? Conspiracy theories sprang up immediately.

An area map of Yellowstone, where many believed the treasure to be hidden

Fenn’s treasure chest from the outside

And then the next major twist in the story happened: In September 2020, Fenn died at age ninety.

Surely that would be the end of the saga, right? The riddle had been solved, the treasure found, and the man who had orchestrated this great game was gone—with no more clues or answers to offer his followers. But if anyone could find a way to stay in the spotlight after death, it was Forrest Fenn. And the story of his treasure continues to take new turns.

A recent Netflix three-part docuseries called Gold & Greed: The Hunt for Fenn’s Treasure chronicles the tale in entertaining fashion. In addition to giving the backstory, it follows a handful of characters who devoted their lives to finding the treasure—and explores with sensitivity how they dealt with the disappointment of not being the one to succeed. The documentary also introduces a startling twist that adds a new chapter to the story of Fenn’s Treasure, thanks to a Fennatic named Justin Posey. It’s sure to have devoted treasure hunters coming back for repeated viewings. (More on that later.)

An ornate gold bracelet that was part of the treasure

But as much as I enjoyed the series, I also had mixed emotions. In some ways, I felt it barely scratched the surface of what Fenn was really like. He was always the most interesting part of the treasure story. And so many of us found ourselves entangled in the hunt because of him more than the treasure itself. To fully understand the enduring draw of the Fenn Treasure, you need to better understand the complicated man behind it all.

The First FatalityIn July 2016, about three years after my first jaunt in search of the treasure, I was back in Wyoming. Only this time, I was at an arts residency I go to every few years, in Ucross, population twenty-six. That’s when it happened: I received a call that a missing person I had been inquiring about had been found and identified. The man was a Fenn Treasure searcher and he was dead, something those of us following the story had assumed. The remains were where I suspected, along the Rio Grande, north of Cochiti Lake in New Mexico. It was six months to the day since he’d been reported missing. For months, the Fenn community had found themselves looking not for treasure but for their fellow searcher, all over the river valley. In the end, the discovery was made by the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers, who happened to be working in the area.

I was stunned, as a journalist following this but also as a fellow searcher. Someone could get killed: The thought had been echoing in my head on and off for years but never enough for me to let go of the story or the search.

I realized it would be near impossible to verify any of Fenn’s most fantastical stories.

Randy Bilyeu was a fifty-four-year-old from Broomfield, Colorado, and the first person who disappeared searching for Fenn’s treasure. Bilyeu’s death was the first reported fatality but not the last. Up until that point, there had been other participants who had nearly lost their lives, but no one had actually died for it.

Fenn, rattled and yet unshaken in his devotion to his hunt, had been speaking to the press like a politician: “When I hid the treasure, this country was in a terrible recession. Too many people were losing their jobs. I wanted to give hope to those who had a sense of adventure and were willing to go searching. I also wanted to get the kids out of the game room and away from their texting machines and out into the mountains and the sunshine.”

In a written statement, he added, “It is terrible that Randy Bilyeu was lost while looking for the treasure. I hope in time the family will heal and move on with their lives. . . . My prayers are with them in this very stressful time.”

More searchers died after Bilyeu: Jeff Murphy of Batavia, Illinois, fell five hundred feet to his death in Yellowstone National Park looking for the treasure in June 2017. That same month and year, Pastor Paris Wallace went missing while searching, and his body was found in the Rio Grande not long after. A month after that, a body was found in the Arkansas River, later confirmed to be that of Eric Ashby; Ashby, like Bilyeu, had moved to Colorado to look for the treasure. Then, in March 2020, Michael Wayne Sexson was found dead by rescuers while his companion lived; the two men were found within five miles of Dinosaur National Monument near the Utah–Colorado border, where they had been rescued a month earlier.

In 2017, I asked Fenn, then eighty-seven, about the rash of fatalities that year. He revealed little remorse, always insisting on the same narrative he fed the press repeatedly: “Three men have died while looking for the treasure, but about 350,000 have searched and gone home safe and healthy, and with wonderful memories and plans to return.”

I asked if he thought about calling it off. “If I call it off, what will I tell all of those who have had great experiences in the mountains and want to continue searching?”

From Fighter Pilot to Art DealerFenn often said to me, in the dozen or so times I spent long days with him, “I’ve created a monster.” He repeated phrases and themes in every conversation, as if he were trying to drive home certain talking points. Mythmaking was always part of his business.

He had never shied away from attention. What better way to get people to buy and read your memoir than to include clues to a million-dollar treasure inside? But the volume and intensity of the interest from Fennatics, and the impact on his family, were more than he’d bargained for. At one point, Santa Fe police arrested a Nevada man accused of stalking Fenn’s granddaughter who appeared to believe that she was the long-sought treasure rather than a chest full of gold. Several times stalkers had been arrested on his property.

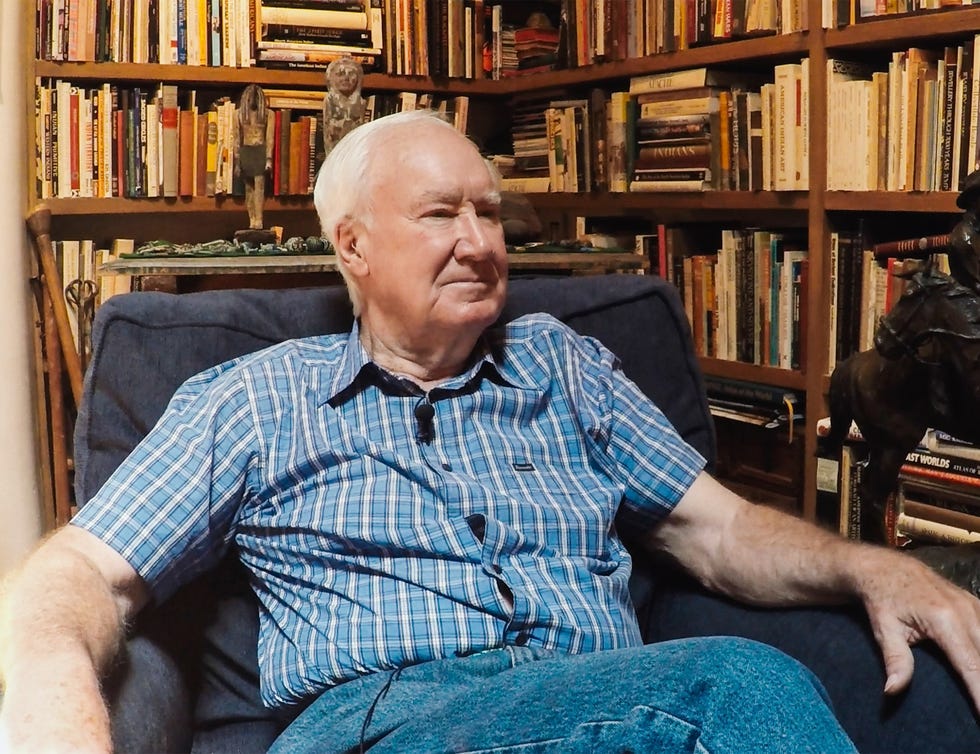

I had lived in Santa Fe for many years when I first met Fenn in the summer of 2013. He was a tall, lanky, white-haired man, always in jeans, always a light-blue button-down shirt, always his turquoise belt—a sort of affable southwestern grandfather type who was hard of hearing and quick to crack jokes. Back then, just a couple years into the hunt, after several of his Today show appearances, Fenn already felt that the whole thing was getting away from him: “The people seem to be crazier in the last while, I don’t know what it is.” I remember him smiling faintly as he said, “It’s going to be interesting what the final chapter says.”

Fenn in his office, which was packed with books, Southwestern art, twentieth-century American memorabilia, and cowboy paraphernalia. Bottom

Before his treasure challenge drew attention, Fenn himself was already a personage in Santa Fe. When you asked him how he got interested in art and discovering hidden treasures, he said without a pause, “Through my father. I found my first arrowhead when I was nine. In Texas. I still have it.”

Fenn was a Texan, from Temple, in the Hill Country, of a relatively modest upbringing. He went into the Air Force, where he trained as a pilot and retired after twenty years, having flown numerous combat missions in Vietnam. Once he got out of the Air Force, he decided, a bit on a whim, to try his hand at business—and a business he knew next to nothing about: art. Along with his wife, Peggy, and two daughters, he moved to Santa Fe. He felt his advantage was that he didn’t know much about what he was getting into—no expectations, no boundaries, nowhere to go but up.

“When I built my business in 1972 in Santa Fe, I met everybody at the door,” he told me. “When I sold it fifteen years later, I didn’t want to go see anybody. I was past my zipper with people coming in the door. That’s called a shelf life. How many encores can you take? For seventeen years, I made $122,000 a month before taxes.” He was, to put it mildly, a great success in town, with many celebrities, from actors to former presidents, as patrons.

One day he took me on a walk through his old property, which had been renamed the Nedra Matteucci Galleries, after the former employee whom he sold it to, along with a stretch limo in the parking lot and a cellar full of wine. We walked through the backyard sculpture garden, full of whimsical Glenna Goodacres and impeccably landscaped hedges, and Fenn paused at the pond to tell me about “Beowulf and Elvis,” his pets. His pet alligators.

I remember his chuckles at my awe. “The secret is to think of everything,” he said.

We lingered longest by the guesthouse on the property. “Steven Spielberg stayed here,” he said. “When President Ford stayed here, that door had to stay open, and then the Secret Service was there with a machine gun pointing right in here. I want you to taste the brandy that Jackie Kennedy left in my guesthouse.” He made good on the offer an hour later, a tiny bottle held up to my face. I didn’t know at that point this was a classic Fenn move, how he won over journalists who he thought would do big pieces on his hunt. I sipped and, well,

it tasted like brandy. He dated it to her stay in 1984, when she was a Doubleday editor in Santa Fe on book business.

Later we got to his home, located rather centrally in Santa Fe, which he maintained was “a one-bedroom”—technically, yes, but one that was also a mansion if square footage and all-around opulence were to be considered. “My wife drew the plans for that house,” he said dismissively, as he did of many things that needed to be seen to be believed in his world. His office had become a bit of a Santa Fe attraction for visitors lucky enough to get in his good graces and gain entry: part museum, part gallery.

“The treasure chest is the greatest caper anyone has ever thought up. It’s better than the lottery.”

Fenn would sit on a normal-sized desk in the middle of a ballroom-sized “office” that was packed full of all sorts of his favorite things: a substantial library (his own self-published books shelved quite prominently), Sundance buffalo skulls from different eras, twentieth-century American memorabilia of all kinds, and paintings from a variety of influences. Southwestern art and Native American and cowboy paraphernalia featured prominently in his aesthetic.

“Everything that I have, I’ve earned,” he told me. “And I’ve earned it by thinking and hustling and using my imagination and common logic. If you have those things, you don’t need an education.”

He launched into a story he was particularly proud of—his connection to Russia. “I told myself that I was gonna go to Russia at the height of the cold war and borrow thirty-six paintings from their museums and bring them to my gallery and open a show, and I did that. That’s called hustling.”

I sat there staring at all the dubiously acquired artifacts—it didn’t take a rocket scientist to wonder if some highbrow grave robbery was involved just to furnish the “office”—and I wondered aloud if there were any lines he wouldn’t cross.

Fenn shrugged. “I sold paintings by Hitler. And I sold paintings by Churchill. I sold paintings by Eisenhower. All of them were pretty good painters.” I paused on Hitler and asked him to elaborate. “Well, one or two paintings, yeah. I mean, I didn’t represent the guy. I think, if I’m not mistaken, I donated the paintings to some Jewish man out there, and they had some kind of big fundraiser thing and they burned it.” As I realized by this point, it would be near impossible to verify any of Fenn’s most fantastical stories.

The mythology around his treasure is what lit him up the most, as if it was the logical ending for his legacy. He was not shy about retelling the origin story: “I was diagnosed with cancer in 1988, and I was standing right here with Ralph Lauren and his wife. And I had something that he wanted. And he said, ‘I want to buy that.’ And I said, ‘Well, I don’t want to sell it.’ And he said, ‘Well, you can’t take it with you.’ And without thinking, I said, ‘Well then, I’m not going.’ And that night I started thinking, I’m going to die—they gave me a 20 percent chance to live three years. If I’m going to die, who says I can’t take it with me? Of course, I’m not going to play by your damn rules; I’m going to play by my own. So for over fifteen years, I filled that chest up with wonderful little things. Gold nuggets, 265 gold coins—most of them are eagles, double eagles. I put my autobiography in the treasure chest. I printed it just as small as they could print. I have to use a magnifying glass to read it. Because I had to roll it up and put it in a little olive jar.

“But anyway, I didn’t want that little olive jar with my autobiography in it to get wet. So I dipped it in hot wax. That seals it. But before I did that, I pulled out a couple, two or three or four hairs, because ten thousand years from now somebody could do DNA. My autobiography also has my thumbprint on it. And I put something else in the treasure chest that’s going to be amazing when somebody finds it. And I decided that because I wanted to know about it, what can I do to influence somebody to make it known? Because the IRS is going to take 50 percent of it. So I put an IOU in there for $100,000—take it to the First National Bank in Santa Fe and here’s an IOU for $100,000. But then I thought, if somebody finds it a thousand years from now, maybe a hundred years from now, there’s no First National Bank, and there’s no account, there’s no point.”

Then he gave his treasure to the public in the form of his memoir, a book most would carelessly skim just to get to the poem, which they would carefully scrutinize for its clues to his fortune. “I didn’t think anybody wanted my book. My parents are dead, so who’s going to buy my book? So I printed a thousand copies. And then it was two weeks later, you know, I’m printing another thirty-two hundred. And then, you know, we printed seventy-seven hundred, and so on. I gave all the books to [local Santa Fe bookstore] Collected Works for free. But they’re putting 10 percent aside. I don’t want to get anything personal out of that.”

Fenn and his grandson, Shiloh Old

He paused. “[My grandson] Shiloh keeps telling me that everybody on the street says that’s the dumbest thing I ever did. But the Collected Works Bookstore has made $700,000 profit. They were going under. And they’ve told me that I’ve saved them.”

It’s tempting to consider Fenn was not just doing this solely to save a bookstore or to gift people an adventure. When I first read up on him, I wondered if he was burying money because, well, he had to. He was iconoclastic and very anti-federal government, and not too long before, he’d been in trouble with the authorities.

In June 2009, Fenn was part of a combined Bureau of Land Management and FBI raid, Operation Cerberus Action, along with another two dozen people in the Four Corners region, in what could be called the nation’s biggest crackdown on black-market Native American artifacts. Twenty-four people were indicted in connection with the theft and sale of the artifacts. Then–Interior secretary Ken Salazar said many of the stolen items, valued at $335,000, came from sacred burial sites. Many of those indicted were antiques collectors like Fenn. The raid resulted in three suicides.

But Fenn was one of the few who managed to achieve exoneration. He convinced prosecutors that he had bought his artifacts through private owners, or else purchased them in the early 1960s, before the current statutes were passed. In 2013, he said, he received a letter from the Justice Department clearing him. He claimed there had been a problem with the initial search warrant for his residence, and one of the terms of the agreement not to prosecute him was that he wouldn’t sue the government.

The search had been a big event in Fenn’s life, for sure. “Twenty-three people were here for seven and a half hours. They went everywhere. Of course, I gave them the key to my vault. I gave them the password to my computer. They took four computers, and when I got them back, they had Federal Express stickers on the computer. They had guns, they had bulletproof vests on. They were going to knock my door down—they had one of these battering rams. I cooperated with them. I told them where my guns were. I gave them the combination to my safe, so, I mean, I wasn’t hiding anything.”

Recounting this story was the only time I saw Fenn tense up and look visibly agitated.

It continued to linger in my brain that the dates he gave for burying the treasure were so close in proximity to Operation Cerberus Action—by some estimates, the same week. Could Fenn have known of the raid? Could the treasure hunt have been his way out of turning over his most valuable items?

In Greek mythology, Cerberus was the multiheaded hound that guarded the gates of the Underworld to keep the dead from leaving. It seemed like a perfect name for this mission.

Years later, however, Fenn reminded me over a Frito-pie lunch that even the fierce Cerberus was captured—outsmarted by the greatest of the Greek heroes, Heracles. “Just took one guy,” he said, squinting at the expansive blue Santa Fe sky. “Some called him a god, but I think he was just the right guy.”

What Makes a True Original?Many people in Santa Fe said they knew Fenn most for selling forged art—that his gallery was indeed a hustle and that he had less local respect than most think. I even had one friend who was gifted a piece from Fenn’s gallery only to have it appraised later and find out it was a worthless forgery.

I decided to ask him about it. There was a Modigliani I’d been admiring in his and his wife’s bedroom, just over their bed.

“There is no original,” he answered simply. “That is the original. He copied the style, not the painting.”

By he, of course, he meant one of the most famous forgers of all time, Elmyr de Hory, whose fakes he also has been a collector of, rather proudly. One day over a steak dinner at the upscale Bull Ring restaurant in town, he told me all about it with little shame. “Museums are full of fake paintings that were given to somebody that got rid of them quick for tax write-offs.”

I asked him what he thought of Santa Fe’s reputation for art—how people are always talking about it being the third-largest art market.

He erupted into laughter. “I originated that. I was talking to somebody and I said, ‘New York, Chicago, Santa Fe, and Los Angeles.’ I didn’t have the slightest idea of what I was talking about, but it stuck. It can’t possibly be true. I made it up.” I nearly choked on my food; to this day it’s a slogan Santa Fe uses constantly.

Addicted to the HuntAs my own obsession with the treasure grew over the years, I tried to cover every track—I even spent a day around Temple, Texas, with two of Fenn’s elderly friends from his childhood. But it got me no closer to finding the prize. Eventually I decided to join the best of the searchers and go to Montana, where my own analysis of the poem told me the treasure really could have been.

That’s how I ended up at the Firehole. Fenn’s favorite searcher and confidant, Dal Neitzel, took me along on an expedition to Montana, my first trip to Yellowstone. He was in his seventies and managed a small TV station in Bellingham, Washington. He was also a documentary filmmaker who was a self-described “search and salvage person.” He managed Fenn’s blog and was seen as a sort of ringleader among the searchers.

We ended up at Fenn’s nephew Chip Smith’s rental property. It seemed notable that one of Fenn’s beloved relatives owned an Arrowhead Lodge in the area, which was basically a tiny quaint town located on the southwest tip of Montana, closely bordered by Idaho and Wyoming, right above Hebgen Lake. It was an area Fenn talked about constantly, his favorite place growing up.

Smith was a towering Montana man—tan, outdoorsy—and was newly married. He introduced us to a cheerful brunette named Amber, his wife. He had a whole three-ring binder devoted to his own ideas about where the treasure was—living right where many thought was the heart of it had not brought him any closer to riches, nor had being related to Fenn.

The plan was that his adult daughter and son, Emily and Aubrey, would take us to Grayling Creek in the morning to search. According to numerous websites, a lot of other searchers had their eye on Firehole Canyon, too.

Emily ended up meeting us with her infant daughter, Aliyah, on her back. We made our way through a trailless creek, where we had to climb several waterfalls along fast current. We had to scramble on all fours at many points from rock to rock. It was slippery and cold and somehow secluded but for us. Emily was completely unfazed with the baby bouncing on her back, used to this terrain—and also quite used to leaving empty-handed, as we did this time as well.

“He was disappointed that it wasn’t going to be buried for nine hundred years,” says a friend. “The fun was over.”

Neitzel drove me to Bozeman to fly out the next day while he continued his search. He had a lot of experience hunting for things that could not be easily found. Our trip together was his forty-first expedition in search of the treasure. Neitzel always drove in his white GMC Safari, a ’99 with 285,000 miles on it, which he called Esmeralda. He freely admitted that he’d become addicted to treasure hunting—specifically this treasure.

Later, when I interviewed Neitzel again, he explained why he was careful not to cross any lines with Fenn about where the treasure was hidden. “I don’t get involved in conversations with Forrest about location of the treasure. If I did that, Forrest would stop talking to me, and I can’t afford that.”

Another time he said this about the search: “I don’t think I’m addicted to it. If I’m addicted to anything, it’s Forrest’s friendship. I think, to me at this point, it’s more about that than it is about the treasure.”

The Ease of Old MoneyAt several points over the years, I would fly in from New York and meet Fenn for lunch at what had become our usual spot, “the deli” in Tesuque. On one such trip, we attended a party in the evening where Fenn introduced me to the actress Ali MacGraw, who could not stop gushing about Fenn. He gave a speech to a few dozen wealthy locals on the Taos artists, an obsession of his.

He didn’t say a word about the treasure. “A whole lot of money in this room,” he muttered to me with a hint of relief. Unlike the general public, these people weren’t mobbing him to ask for clues. It didn’t interest them. They didn’t need it. This was Santa Fe’s old money, the world he’d snuck into.

Justin Posey spent years searching for the Fenn Treasure, only to come up short. But he acquired some of the pieces at auction. And now he’s buried a new treasure chest with some of Fenn’s artifacts along with additions of his own.

Celebrities were easy for him in that way, Fenn told me many times. One of the few people, of the four or five, who had seen the treasure before it was buried was his friend Suzanne Somers. They’d known each other for decades. She loved the whole treasure concept. “The treasure chest is the greatest caper anyone has ever thought up. It’s better than the lottery,” she wrote to me in an email before her death.

“I know what’s in it, I’ve touched it, looked through it over the years as he has lovingly filled it. . . . What I love most about the treasure chest is that it will keep Forrest alive long past chronology. He wants to stay around to see how it turns out, and anything that keeps Forrest Fenn on this planet longer is fine by me.”

An Unexpected TwistIn the depths of the pandemic, among the many disasters of 2020, one summer day my Google alert told me that the treasure had been found. It seemed to surprise everyone, even though we all knew the day would come. Fenn’s close friend Doug Preston, a local writer, told me the only sign of decline he had noted in Fenn was in his reaction once the treasure was found. “He sounded really discouraged to me that it was found. I mean, that’s how I interpreted it. I think he was disappointed that it wasn’t going to be buried for nine hundred years. I got the sense that he was a little bit let down by it, and I think that that disappointment carried through. The fun was over.”

But, of course, the story wasn’t over. Many of the Fenners were stunned and angry that the mystery had been yanked from their lives, so they promptly began making up new theories: Fenn had moved the treasure so that it wouldn’t be found and then faked the discovery. Or the treasure had never been buried in the first place. The pair of photos that Fenn released didn’t mollify them, nor did Fenn’s disclosing that the chest had been found buried in Wyoming. It didn’t help that the man who discovered it wanted to remain anonymous, which seemed highly suspicious to the distraught Fennatics.

Shortly after Fenn’s death, in late September 2020, an anonymous three-thousand-word post called “A Remembrance of Forrest Fenn” appeared on Medium from a man who called himself The Finder of the treasure. One part obit, one part a chronicle of his experience discovering the treasure after two years of intense searching, it did nothing to quell the conspiracy theorists. The tone was so Fenn-like, to my eye, that I even found myself wondering if Fenn had hired someone to write it and publish it after his death. It would be a very Forrest Fenn thing to do, after all. The Finder wrote: “As for the legacy of Forrest’s chase, I suppose it is in many ways in my hands, as wrong as that feels. To be honest, I’m not sure what to do.”

A few months later, a thirty-two-year-old medical student named Jack Stuef revealed himself to be The Finder (as he labeled himself) in an interview with Outside magazine, and Fenn’s family confirmed that he was the man who’d discovered the treasure. Stuef said he’d come forward because his name was about to be revealed in a lawsuit. Some Fenners began criticizing Stuef as being in on a conspiracy of one sort of another, validating his concerns about being identified publicly in the first place. In December 2022, the treasure was put up for auction and 476 artifacts in the collection sold for a combined total of more than $1.3 million.

One of the buyers of the treasure, apparently, was Justin Posey, a dedicated searcher who is one of the main characters in Gold & Greed, the Netflix show. And it is Posey who has taken it upon himself to reboot the Fenn Treasure hunt with one of his own.

In a major twist, Posey, a forty-two-year-old software engineer, said in the docuseries that he has hidden his own buried treasure. What’s more, he revealed that he has embedded clues in his elaborate background setup—without consulting the series’ producers—about where the treasure is hidden. But there are more clues, he says, in his own book, called Beyond the Map’s Edge. Posey says his treasure chest contains a mix of items he had collected over the years and pieces from Fenn’s treasure. He has declined to give too many details or to put a monetary value on the booty, for fear of having his words used against him in a future lawsuit.

Watching Gold & Greed, I found Posey to be a compelling and sympathetic character. In fact, he was the high point of the series for me. The Fennatic in me also relates to what he’s done: I understand wanting to make sure the hunt never ended—even though I am not sure that’s what Fenn wanted at all. As for me, I don’t see myself getting caught up in the old fever. And I wonder if Posey’s treasure will garner the same passion. Without a charismatic trickster from eras past, does a treasure hunt even work? We’re about to find out.

esquire