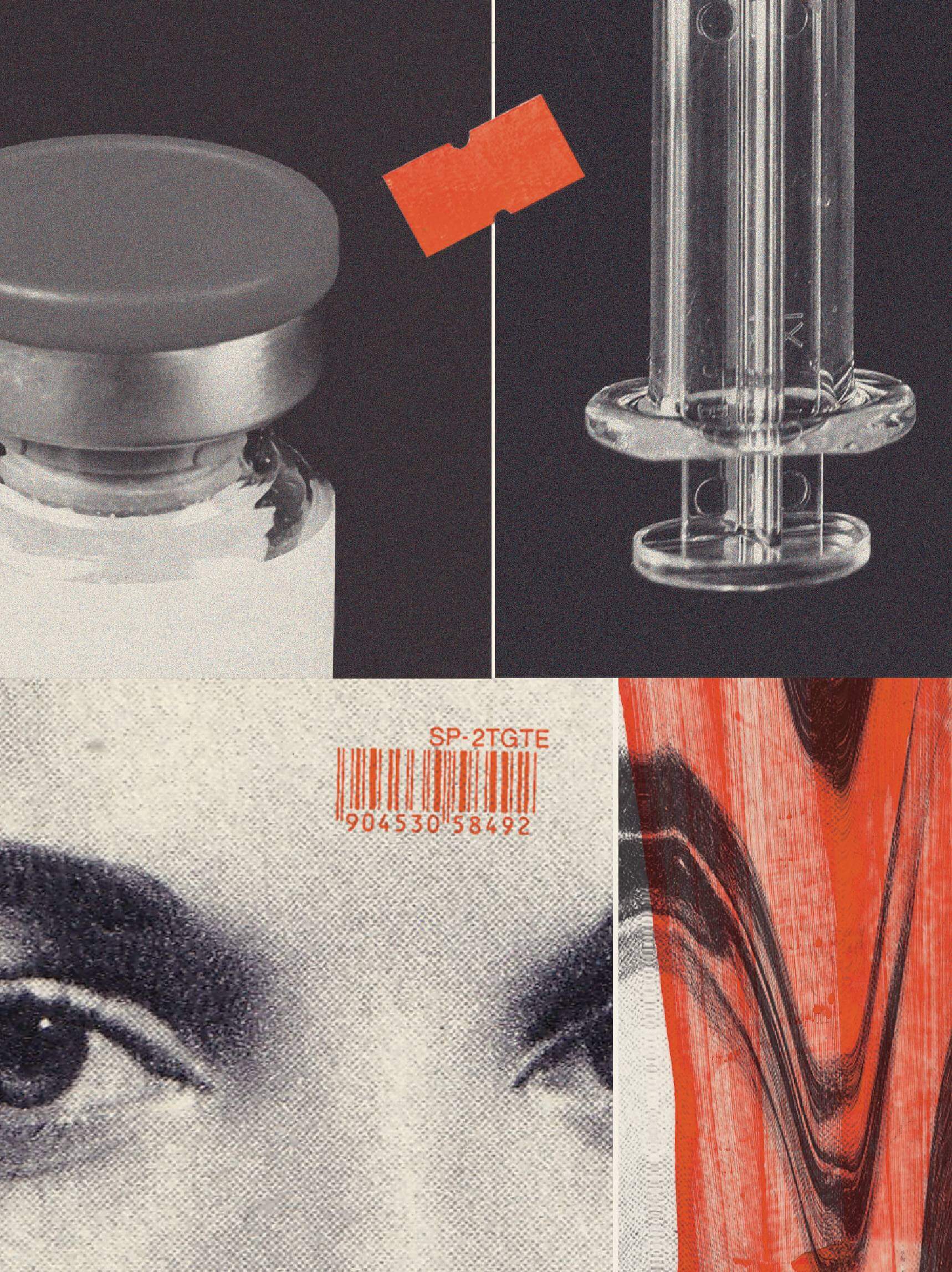

Is That Filler Legit, or Was It Bought on Alibaba?

In September 2022, a woman went looking for lip filler and found herself at a Skin Beauté medical spa in Randolph, a suburb about 15 miles south of Boston. There, she encountered Rebecca Fadanelli, the glamorous 30-something owner, who told her she was a nurse. According to court documents, the woman asked what substance was being injected into her lips, but Fadanelli didn’t answer directly—she simply said that she had purchased the products from Brazil and China. Then Fadanelli also injected filler in between her eyebrows, allegedly without her permission.

Soon, bumps started to form in the woman’s lips, and she experienced tingling on her forehead where she had been injected. The client asked Fadanelli for a copy of the prescription, but Fadanelli never provided one. Suspicious, she searched for Fadanelli’s nursing license on Mass.gov, but learned she wasn’t registered. Her next call was to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA): a single complaint that would help uncover a raft of shocking claims about the med spa’s practices—and highlight serious concerns about the entire industry.

When clients happened upon Fadanelli’s two Boston-area Skin Beauté locations, the spas looked luxe and legit. They were spacious, with chairs and couches covered in blue velvet, glittering chandeliers hanging overhead, and tidy skin care product displays, including some from Fadanelli’s eponymous line. On social media—tagline: “Beauty is not in the face, beauty is a light in the heart!”—Fadanelli, whose vibe was more Miami than Massachusetts, with the long blonde hair, deep bronze tan, and exaggerated trout pout of an influencer, presented an enviable life, driving a white Range Rover, and often posing in a white lab coat, giving her a veneer of expertise. In one video, she sampled her own offerings, filming as a clinician massaged a micropigmentation pen over her ample lips.

It was best not to look too closely. Fadanelli claimed to have a degree from Harvard, which had been misspelled as “Havard” in her online list of credentials, according to an FDA criminal investigative agent’s court filing. And she made vague claims that she was “qualified as a Licensed Instructor by the Massachusetts State Council.” Criminal authorities allege that behind the glitzy facade, Fadanelli was concealing a very dirty secret. When she was arrested in November 2024 for allegedly performing thousands of illegal counterfeit injections on clients over three years, Fadanelli left former patients to wonder what, exactly, she had injected into their faces—and why no one stopped her.

The Fadanelli case is very much a scenario that dermatologists have warned about, as the number of medical spas in the United States has increased sixfold since 2010. As of 2024, there were an estimated 10,488 med spas across the U.S., up from 8,899 in 2022. These beauty boutiques are exactly what they sound like—one-stop shops that combine medical skin treatments with the blissed-out pampering of a spa experience. Women across America now visit med spas to casually fork over hundreds or even thousands of dollars for a range of procedures: Botox and fillers like Sculptra, Restylane, and Juvéderm, which provide plumping volume to counteract sag and wrinkles; laser treatments for skin and body hair issues; microneedling and chemical peels; and body contouring treatments like CoolSculpting, which eliminates unwanted fat cells by freezing and expelling them.

“One complained about droopy eyelids; another flagged little balls forming in her lips. Yet another reached out about a hard lump she had found. Her eyes, she said, appeared to be sinking into her face.”

The possibilities to indulge seem both endless and increasingly convenient, from Botox bachelorette parties to IV drip pop-ups in hotels and casinos. Alex Thiersch, founder and chief executive of the American Med Spa Association (AmSpa), recently told Bloomberg Businessweek that med spas really started to take off around 2010, when interest rates were low, regulations were being loosened, and nipped, tucked, and buffed reality TV stars were becoming ubiquitous. Major advancements in cosmetic treatments over the past two decades—Botox was first approved by the FDA for its use in 2002—have also played a role.

The businesses can be extremely lucrative: The average medical spa brings in nearly $1.4 million a year in revenue, according to AmSpa. The barriers to entry are relatively low, especially for those who already have a relevant professional license, such as nursing or aesthetics. For Fadanelli, opening med spas may have offered a path for rebuilding her life post-divorce. She was born in the city of Maringá, Brazil, and moved to the U.S. in 2003, when she was in her late teens. Her mother encouraged her to move home—Massachusetts was so far away—and Fadanelli was on the verge of acquiescing. Then she met Marshall Daley. In 2009, shortly after she and Daley started dating, Fadanelli got pregnant, and the pair decided to get married. But after their daughter was born, things turned rocky. Fadanelli filed for divorce in March 2014, and an ugly court battle ensued.

When the dust finally settled, Fadanelli seemed to move on with her life. She had been working at a medical spa, but she realized she wanted to branch out on her own. And so, in 2018, Fadanelli founded Skin Beauté, first in Randolph, followed by a second location in South Easton, another suburb south of Boston. She provided a range of services: facials, laser treatments, microblading, fillers, and Botox, but according to a court filing, not all of those services were legit. Since at least March 2021, prosecutors allege that Fadanelli had been illegally importing and administering counterfeit prescription drugs, including Botox, which allowed her to offer treatments to clients at much lower rates than her competitors. She allegedly logged on to Alibaba, the online Chinese Amazon-esque marketplace, and ordered boxes of counterfeit Botox from China for $50, instead of paying around $650 per box for the real thing. Employees at Skin Beauté seemed to trust that Fadanelli knew what she was doing—after all, she told them she was a nurse.

Skin Beauté’s Easton location.

It seems obvious that—as the name suggests—medical spas offer procedures with real risks that are best performed by qualified medical personnel. Despite this, there is no single national standard for medical spas; each state is governed by different regulations. In general, med spas across the U.S. are required to have some degree of medical oversight, and in some states, only doctors are permitted to own such businesses. Patrick O’Brien, legal counsel at the American Med Spa Association, says that med spas generally aren’t regulated any differently from a medical practice when doctors own the business and administer the treatments deemed more invasive.

But regulations differ on how much supervision is required by an MD. Some states, including Massachusetts, allow nurse practitioners and physician assistants to administer injectables, but only allow non-prescribers, like nurses, to administer them with a valid prescription or medication order. Rhode Island passed a law called the “Medical Spa Safety Act” in June, which mandates that med spas be licensed health care facilities under the state’s department of health and have a licensed medical director trained in cosmetic procedures. There are other nuances: New York is the only state where laser hair removal is completely unregulated, for example.

Many doctors argue that their education and strict licensing standards make them the best choice to administer invasive treatments—even if that pushes up the cost to consumers. It’s worth it, they say, to avoid the potential hazards that can come with a less-qualified clinician. Yet a 2023 study by the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association found that a supervising physician was only present during injection treatments in 38 percent of med spas, and only 46 percent of spas reported notifying a physician when complications arose. In addition, a supervising physician’s board certification was in dermatology or plastic surgery less than 22 percent of the time.

And even minimally invasive skin tightening procedures have a significantly higher rate of complications at med spas compared to doctors’ offices—77 percent versus 0 percent, according to a 2023 study in Dermatologic Surgery, an academic peer-reviewed journal. A 2020 survey of members of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery found the most commonly cited complications from med spa treatments included burns, discoloration, and “misplacement of product.”

As millions of women across America continue to spend money on this over $20 billion business—which, according to Brenton Way, a digital marketing agency, is expected to reach over $49.4 billion by 2030—tales of lax oversight and unqualified clinicians at med spas are mounting. In July 2023, 47-year-old Jenifer Cleveland, a mom of four in Fairfield, Texas, died after receiving an intravenous pick-me-up at a med spa. The IV contained a vitamin B complex, including ascorbic acid, cyanocobalamin, and TPN electrolytes—a solution that requires a prescription and is typically used in hospital settings because it may cause patients to overdose. It was reportedly administered by an unlicensed med spa practitioner who wasn’t equipped to help when Cleveland had trouble breathing.

In another terrifying case, a med spa owner named Maria de Lourdes Ramos de Ruiz was arrested in New Mexico for practicing medicine without a license, and other charges, when it was discovered that some of her clients contracted HIV after receiving cosmetic platelet-rich plasma microneedling—also known as “vampire facials”—at her VIP Beauty Salon and Spa in Albuquerque. The spa was unlicensed, as was Ramos de Ruiz, according to a press statement made by the then New Mexico attorney general. In 2018, a client of Ramos de Ruiz who was in her 40s tested positive for HIV; ultimately, three more HIV-positive clients were discovered, according to a Centers for Disease Control investigation into the case, and one of them had already passed the virus to her partner.

When investigators descended on the Albuquerque clinic, they found a house of horrors: unwrapped needles, tubes of unlabeled blood on a kitchen counter, and unlabeled syringes next to food in the fridge, according to the attorney general’s statement upon her sentencing. Ramos de Ruiz pled guilty to practicing medicine without a license in 2022, and was sentenced to three and a half years in prison.

Concerns about counterfeit injectables have also increased in recent years, and it can be hard for consumers to distinguish what’s legit. The FDA, which regulates prescription drugs like Botox and medical devices such as some fillers, put out an alert in May 2024 after finding counterfeit neurotoxin administered in med spas in multiple states, resulting in reports of blurred vision, shortness of breath, incontinence, and even hospitalization. Another FDA notice in December 2023 warned of severe infections and even skin deformities acquired from counterfeit injections intended to dissolve fat. Further, in April 2024, the New York City Health Department warned about counterfeit Botox after several women became ill; at least one of them received the injection from an unlicensed provider. Additional cases linked to counterfeit Botox have been reported in California, Colorado, Florida, Illinois, Kentucky, Nebraska, New Jersey, New York, Tennessee, Texas, and Washington.

While some consumers might assume this kind of activity only occurs in the sketchier corners of the industry, this past January, silver-haired Joey Grant Luther, an aesthetician with his own glitzy New York City med spa, was arrested amid allegations that the Botox he illicitly administered was actually counterfeit product he ordered from China. Prosecutors allege that his injections left patients with botulism, impaired vision, and other health concerns.

“If you have a material and it’s never been tested on humans, anything could happen.”

According to a 2020 study in Dermatologic Surgery, 41 percent of surveyed members of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery and the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery say they have encountered counterfeit injectables, and nearly 40 percent have treated patients who come to them after suffering adverse events from exposure to counterfeits. While many of these fakes originate in China, U.S. customs has also apprehended shipments from Bulgaria, Spain, South Korea, and Hong Kong.

Phony injectables might be unsterile, contain unknown dosage levels that could be dangerous—such as deadly levels of botulinum toxin, the active ingredient in Botox—or even contain a mystery ingredient or material intended for other purposes, such as tire sealant. “If you have a material and it’s never been tested on humans, anything could happen,” says Scott T. Hollenbeck, MD, president and chair of the Department of Plastic and Maxillofacial Surgery at the University of Virginia School of Medicine. In 2016, a Texas woman was sentenced to five years in prison after pleading guilty to killing a patient she injected with fake Botox. The shots turned out to contain hardware-store-grade silicone.

Between March 2021 and March 2024, Fadanelli’s “Botox” and filler appointments brought in revenue of $933,414, according to prosecutors. But her plan hit a major snag in October 2023, when she flew into Boston’s Logan Airport after a visit to Brazil. A court filing states that, when searched by U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Fadanelli was found to be carrying several vials labeled as the filler Sculptra, as well as vials of bacteriostatic water used to dilute medication, and other vials of liquid labeled in various languages. All were determined by the FDA to be misbranded or unapproved goods and were seized. Between November 2023 and March 2024, customs also seized six shipments of goods from China addressed to Fadanelli’s clinics and her home. When the customs officers opened the packages, they found boxes labeled Botox, Sculptra, and Juvéderm, all suspected of being misbranded or unapproved. They notified Fadanelli of the seizure, telling her they wouldn’t be released.

Fadanelli began trying other methods. In December 2023, she told her Chinese supplier to ship via FedEx, which prosecutors believe she thought might evade detection. That didn’t work, either—the confiscations continued. So in February 2024, she allegedly advised her supplier to change the name being used to ship the goods and to also try shipping the products to her home and to a clothing boutique she also owned called Linda Concept. (“Linda” means beautiful in Portuguese.) But customs seized those packages, too. Fadanelli began storing the counterfeits at home and bringing them to work as needed in a silver briefcase and lunchbox, according to a statement to investigators from a former employee.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents stand next to cargo seized at at Los Angeles International Airport for physical inspection.

An FDA agent alleged in court filings that on one occasion, Fadanelli’s supplier tipped her off about quality control issues, particularly the potency. “This batch botox strong…add 3ml saline for try…please do not add too less saline it will be injection too much,” wrote the supplier in February 2024. And over time, Fadanelli started to hear from clients who were concerned about the quality of her work: One complained about droopy eyelids; another flagged little balls forming in her lips. Yet another reached out about a hard lump she had found. Her eyes, she said, appeared to be sinking into her face.

Unbeknown to Fadanelli, the feds had been investigating her for months, tipped off by the client with the lumpy lips and tingling forehead. The case had landed on the desk of Officer Brian Hendricks, a special agent with the FDA Office of Criminal Investigations, who, while investigating Fadanelli, discovered the reason the client hadn’t found a nursing license in the state database. Fadanelli was not in fact a nurse as she represented, but a registered aesthetician—a licensed skin care professional with 600 hours of training coursework in a board-approved school. An aesthetician is certified to provide services like facials and microdermabrasion, but not legally permitted to administer cosmetic injections in Massachusetts—as in many states. Neither of her med spa locations was licensed by the state, as required, according to the department of public health.

Hendricks wanted to catch Fadanelli in the act, so he recruited a confidential informant. On April 9, 2024, the informant arrived for a Botox consultation at Skin Beauté’s Randolph office, outfitted with a hidden camera and recorder. There, she was introduced to Fadanelli, who offered to administer Botox at their next appointment for $450, according to the court filing.

Federal agents started surveilling Fadanelli. They were particularly interested in the silver briefcase and lunchbox she seemed to be carrying every time she stepped out of her Range Rover. On the morning of June 28, 2024, it was go time. They raided both locations of Skin Beauté, confiscating files, computers, and other devices, along with counterfeit Juvéderm, Restylane, and Sculptra that Fadanelli had been carrying. Fadanelli denied that she administered injections, but admitted she bought Botox and fillers off Alibaba. She was arrested on November 1, 2024, and charged with importing merchandise contrary to law, and the sale and dispensing of counterfeit drugs. (Attempts to contact Fadanelli directly and through her attorney did not receive responses. She pleaded not guilty to all charges.)

Amid a growing number of cautionary tales, efforts are underway to reform and standardize the med spa industry. In June, Texas lawmakers enacted “Jenifer’s Law,” named after the woman who died of sudden cardiac arrest after receiving an intravenous infusion. When the law takes effect in September, it will require that physicians, registered nurses, or physician assistants supervise elective IV therapy outside of a traditional medical setting.

A handful of states have attempted to tighten regulations and guidelines, and focus more on safety and training. The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) has created sample legislation suggesting that medical spas should be overseen by qualified and licensed doctors who are on-site for invasive procedures, even when administered by another employee, such as a nurse, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant. AAD guidelines also suggest that medical spas have a notice on the door of the facility, and online, indicating the name of the supervising physician and the days that physician is there. Clinicians should be required to wear photo IDs that identify them by name and qualification, and any credentials issued by relevant bodies should be searchable on public databases. “You’re getting someone who is well-educated and the authority on what filler to use, what goes where, how much to inject, and how to handle a side effect,” says Susan C. Taylor, MD, president of the AAD. “You really get what you pay for.”

Standards are one thing; enforcement is another. Med spas are commonly cited as a regulatory gray zone, with insufficient inspection and oversight protocols. Even in states like Massachusetts that require a high level of physician involvement in med spas, it’s unclear whether anyone actually adheres to those rules. Another problem, O’Brien adds, is that the licensing agencies who inspect spas focus on cosmetology rules and wouldn’t necessarily look for medical violations. In Fadanelli’s case, Skin Beauté was inspected at least once: In June 2023, an inspector with the Division of Occupational Licensure visited the South Easton location and found an infraction regarding “syringes in the aesthetics room.” The citation resulted in a $100 fine, barely a hiccup, for what was listed as a “sanitary/sterilization” violation. There’s no evidence Fadanelli’s credentials or products were assessed at that time, and the Massachusetts Office of Public Safety and Inspections did not respond to direct questions about the incident. Both Skin Beauté locations continued to operate while Fadanelli was under active investigation by the FDA.

Fadanelli is being represented by a public defender and faces up to 20 years in prison. “The type of deception alleged here is illegal, reckless and potentially life-threatening,” said then Acting United States Attorney Joshua S. Levy, in an emailed statement.

But the fight against counterfeit injectables remains an uphill battle, and the CDC notes that most counterfeits are purchased through online marketplaces and administered by clinicians without the proper licensing, typically in casual settings, such as home Botox parties. While Customs and Border Protection tries to intercept shipments of illicit drugs, the results are mixed. “Our supply chain has been infiltrated with counterfeit Botox—historically, presently, and will be in the future,” George Karavetsos, former director of the FDA’s Office of Criminal Investigations, told The New York Times last year. Consumers need to be vigilant.

Oma N. Agbai, MD, associate clinical professor of dermatology at the University of California, Davis School of Medicine, recommends that clients ask to be shown the box for any injectable. “Say, ‘Oh do you mind showing me the packaging? Can I see the lot number and expiration date?’” she says. “That’s a very basic question—if they can’t show you that, it’s a red flag.”

This story appears in the September 2025 issue of ELLE.

elle