Teen mental health: When to seek help and what parents can do

Lucy says she's always been a bit of worrier, but two years ago she began to get anxious and started having panic attacks.

"I didn't know what was happening and my parents didn't either," says the 15-year-old. "It was scary. The attacks would occur without warning. It got worse and I began to have them in public."

Lucy started missing a lot of school and stopped socialising. She says it was hard for her parents to see her struggling. "We didn't know what to do or where to go."

For six months, she tried to manage her anxiety herself, but eventually the family decided to pay for a talking therapy called cognitive behavioural therapy.

Lucy says it has made a huge difference. While she still has panic attacks, they are much less frequent and she is back attending school and doing the things she enjoys.

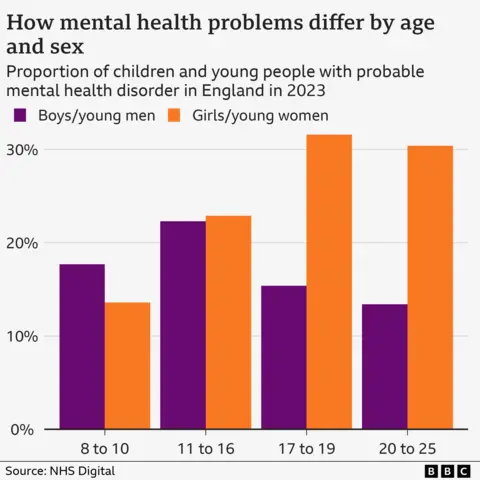

Lucy's story is far from unique. NHS figures suggest one in five children and young people aged eight to 25 has a probable mental health disorder.

The teenage years are when problems become increasingly common as young people grapple with the challenges of growing up, exam stresses, and friendships and relationships.

There are biological reasons too that make emotional health problems more likely, says Prof Andrea Danese, an expert in child and adolescent psychiatry at King's College London.

"Teenagers' brains don't develop all at once. The part that processes emotions matures earlier than the part responsible for self-control and good judgement. This means young people can feel things very intensely before they've fully developed the ability to manage those feelings, which helps explain some of the emotional ups and downs parents often see."

The zenith, he says, is adolescence, when emotional reactions are further heightened by hormones and changes to the internal body clock which impact sleeping patterns.

So, what constitutes normal emotional challenges - and when should teens and their parents be worried and consider seeking professional help?

Prof Danese says he understands why many find this difficult to judge. He considers the following as normal teenage emotional traits:

- Periodic irritability and moodiness

- Occasional social withdrawal or desire for privacy

- Anxiety about social acceptance or academic performance

- Experimenting with identity and independence

- Emotional reactions that seem disproportionate

Providing these are not interfering too much with daily activities, parents should feel able to support their children, he believes.

The most common problems teenagers experience are low mood and anxiety. For low mood, Prof Danese says, maintaining healthy routines around eating, sleeping, being active and keeping in touch with friends and family is important as is planning activities that your child enjoys, such as trips out or playing a sport.

"And help them identify, break down and try out solutions for problems that may have arisen," he adds.

For anxiety, calming techniques are helpful, he says. These can include breathing exercises, grounding, whereby you concentrate on the environment around you and what you can see, touch and smell, and mindfulness activities.

"It's important to avoid the trap of providing unnecessary reassurance," Prof Danese says. Instead, alongside teaching calming techniques, parents should discuss and test out feared situations. "To reduce worries, it can help to write them down or talk about them at a special 'worry time' once a day."

Stevie Goulding, who runs the parent helpline for Young Minds, says anxiety is the issue they get the most calls about.

"Many children will have bouts of anxiety and even panic attacks. It's difficult for parents. They can easily find themselves lacking in confidence and judgement about what to do. We get lots of calls from parents in that position. When they see their child struggling it can make them question themselves and they just don't know where to turn.

"The main advice we give parents is to communicate with their children. Give them permission to talk about what is bothering them – and if they don't want to talk to them, ask if there is someone else they would prefer to talk to."

Ms Goulding also recommends talking to your child's school as they may have noticed things too.

But she adds: "Children need to be given space – avoid the temptation to rush in and try to fix things. Just reflect what they are saying and listen."

Child psychologist Dr Sandi Mann agrees, saying parents have an understandable temptation to want to resolve whatever issue their child is facing when that is not necessarily the best solution.

She says instead parents should help teach and build resilience in their children – and has written about this for the BBC.

She recommends parents:

- Explain setbacks happen to everybody, giving examples of things that have gone wrong in your own life

- Embrace mistakes

- Empower them to make their own decisions, stressing they are largely responsible for their own happiness

- Challenge their beliefs, particularly black-and-white thinking and catastrophising

"I think we sometimes can create the impression that children and young people are not able to solve their own problems when we are rushing them to get help or turning to medication."

But Dr Mann and Prof Danese both stress parents should not shy away from asking for professional support when needed.

"There's nothing to be ashamed of," says Dr Mann. "We just need to know when to try to solve problems and when to get help."

They both highlight similar behaviours that should act as a trigger for parents to get help. These include:

- Self-harm and suicidal thoughts

- Extreme changes in eating or sleeping

- Dramatic personality changes and expressions of hopelessness

- Significant interference with daily functioning, such as going to school or socialising

- Prolonged withdrawal from activities that were once enjoyed

Dr Elaine Lockhart, chair of the Royal College of Psychiatrists' child and adolescent faculty, says parents should feel comfortable about broaching mental health with their children and asking for help.

"We know lots of children struggle. The idea that the school years are the best years of your life is a fallacy."

But with long waiting times for NHS child mental health services, knowing where to go for help is not straightforward, particularly if you cannot afford private therapy.

The first point of call is normally your GP or mental health support teams that are linked to schools in some areas. As well as referrals to NHS mental health services, they can put you in touch with local organisations and charities that can provide support.

"Schools themselves can also help – some have counselling and support services," says Dr Lockhart.

"But I think parents can underestimate the role they can play even if their child is waiting for support or actually getting therapy or treatment. The home is where they will spend most of their time – so parents are a big part of the solution."

If you need mental health support the following links provide information about how to get help:

BBC