The enigmatic dragon man was not a new human species, but a Denisovan

After 146,000 years and a far-fetched history, a team led by Chinese scientists and a Swedish Nobel Prize winner in medicine announced this Wednesday that it has successfully recovered DNA from a fossil assigned to a new human species, Homo longi , popularly known as the dragon man . This exceptional breakthrough overturns one of the last major discoveries in human evolution. It turns out that the longi is not a new human species native to Asia, but a Denisovan.

Denisovans are the only human species identified not by the shape of their bones and skull, but by DNA extracted from tiny bone fragments found in Denisova Cave in Russia. It was the tip of a little girl's pinky finger that discovered this new human group, and subsequent samples revealed them to be a sister species to the Neanderthals. Genetics also showed that they had sex and fertile children with Neanderthals, and with our own species, Homo sapiens . Today, many Asians carry a small percentage of Denisovan DNA within them. Among the inherited genes are those that allow people to breathe without suffocating in the highest altitudes on the planet, such as the Himalayas, and others that improve metabolism in extreme cold, present in the Inuit of the Arctic.

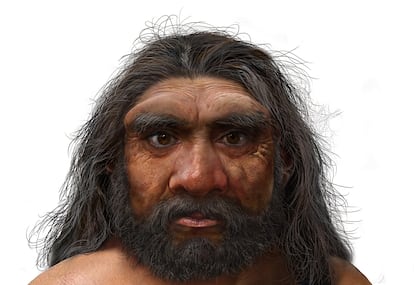

What no one yet knew was what these humans' faces looked like, as no complete skulls were known. The study published this Wednesday changes this forever, showing that the Denisovans were robust people, with large teeth and very pronounced eyebrows. They probably also had a brain equal to or larger than that of modern humans, judging by their cranial capacity of 1,400 cubic centimeters.

The molecular identification of this first skull confirms that the Denisovans were a successful group, surviving for tens of thousands of years in very different environments in Asia, from the steppes of Siberia through the Himalayas to the coasts of eastern China, including Taiwan. In these and other places, such as Laos, fossils have been found that possibly also belong to this third branch of humanity, as suggested by the authors of the study, published today. in Cell .

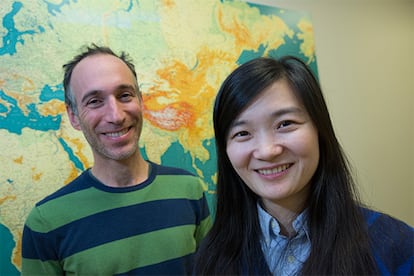

The Homo longi species must therefore be discarded, and we must even stop thinking about species when talking about human evolution, explains to EL PAÍS Svante Pääbo , a world pioneer in ancient DNA analysis, Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2022, and co-author of the work. “The concept of species is no longer useful when talking about Neanderthals and Denisovans. They are closely related groups that mixed and had fertile children among themselves, and also with our species. So we prefer to talk about modern humans [us], Neanderthals and Denisovans,” he explains in an email.

The team has focused its analysis on the Harbin skull , whose story begins in 1933, when the bloodthirsty Japanese troops invaded China. A worker collaborating with the Japanese in the construction of a bridge near the city of Harbin came across the fossil, hid it from his bosses, and kept it in a well for his entire life, since after the war he did not want to reveal to the communist authorities that he had collaborated with the invaders. In 2018, the man's grandchildren recovered the fossil and took it to the paleoanthropologist Qiang Ji, who received it as a treasure, because it had survived the Japanese invasion, a civil war, the communist dictatorship, Mao's Cultural Revolution, and the rampant fossil trafficking in China. The problem was that there seemed to be no way to confirm its provenance or its age.

Four years ago, Ji's team managed to date the skull thanks to the mud stuck to its nostrils. It was 146,000 years old and identical to the sediments beneath the Harbin Bridge. The researchers announced that the fossil represented a new "sister" species of Homo sapiens , a scientific coup that didn't convince all experts .

The first author of the new work is 42-year-old Chinese paleoanthropologist Qiaomei Fu, whose participation has been key. The scientist learned the best techniques for analyzing ancient DNA in Pääbo's laboratory at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, and in that of American David Reich at Harvard University, another leader in this field. The researcher now leads her own team at the Institute of Paleoanthropology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing and collaborates with Qiang Ji's team. After several failed attempts to isolate DNA from bone, the team managed to rescue mitochondrial DNA from the tartar accumulated on one of its molars. The results confirm that the dragon man is actually a Denisovan related to its Siberian counterparts.

Fu led another study this Wednesday, published in Science , in which they managed to recover 95 proteins from that same skull. This biological material, more resistant than DNA over time, confirms the theory that it is a Denisovan, and represents a world record: they have recovered more proteins from a single human fossil than all similar studies conducted to date.

“ Denisovans are the new star of human evolution,” summarizes CSIC paleoanthropologist Antonio Rosas , who did not participate in either study and who emphasizes their importance. The key, he explains, is that for the first time these humans have “a skull associated in a seemingly indubitable way,” that is, a face. “This first Denisovan par excellence,” he explains, “can be used to analyze other classic and enigmatic fossils, such as the Dali skull, some 270,000 years old.” The human fossils from Hualongdong , in eastern China, dating back 300,000 years, and the juluensis , or big-headed people , who lived in northern and central China at the same time, could also be Denisovan. A few weeks ago, another team managed to recover proteins from a jawbone found in Taiwan. The analysis revealed that it was from a Denisovan, which may have lived in two eras in which this territory was connected to continental Asia. It could be between 190,000 and 130,000 years old, or between 70,000 and just 10,000 years ago.

British paleoanthropologist Chris Stringer , co-author of the study that established the dragon man as a new species, refuses to give up on his thesis. “These two articles are potentially very important, although a more complete assessment will be necessary by experts in ancient DNA and proteomics,” he responded to EL PAÍS in an email. “I have been collaborating with Chinese scientists on new morphological analyses of human fossils, including the one from Harbin, and this work makes it increasingly likely that this is the most complete Denisovan fossil found so far, and that Homo longi is the appropriate species name for this group.” “Another name, Homo juluensis , was recently coined to include Denisovans but not Harbin, so it is unlikely to be suitable for either. Our analyses suggest that most large-cranial humans of the past 800,000 years can be classified into one or other of the following groups or species: Asian Homo erectus , Heidelbergensis , Neanderthals, sapiens, and Denisovan- longi ,” he adds.

It remains a mystery when and where Denisovans and Neanderthals appeared, and who their ancestors were. The most likely scenario is that they were some variant of Homo erectus , the longest-lived human species and the first to leave Africa walking on two legs. Sapiens also descend from the erectus, although our origin is confirmed to be in Africa.

“The million-dollar question,” says Rosas, “is why the Denisovans of Asia, like their Neanderthal brethren in Europe, became extinct around 40,000 years ago, just as large groups of Sapiens arrived from Africa. That period of ice ages was extremely harsh, and caused the gradual extinction of mammoths and other large mammals, the hunting of which Neanderthals and Denisovans lived. Despite becoming extinct in Europe several times, Sapiens thrived, becoming the only human species on Earth. The CSIC scientist believes, like other experts , that the key lay in “the new neural capacities of Sapiens involved in creating and maintaining large-scale cooperative networks”; a characteristic that remains to be demonstrated in the other two branches of humanity.

EL PAÍS