Han Kang, Nobel Prize winner in literature: 'I don't want to stop writing or become stupid'

The Nobel Prize winner for literature spoke to BOCAS magazine about horror and political massacres in her two new novels; about The Vegetarian and her life after the Nobel Prize; about the death of her older sister, her intense relationship with snow for seven years, about characters who lose their fingers and about strange dreams that, once she wakes up, she writes down in a notebook and can become the seed of a story. She is Han Kang. Exclusive interview by BOCAS.

On the computer screen we see a bright, airy room with a skylight through which an intense white light falls. Below us, we are greeted by a smiling Han Kang (Gwangju, 1970), the latest Nobel Prize winner, from South Korea, who gives BOCAS one of her first world interviews after receiving the award in Stockholm last December. Han Kang has worked in various jobs, although she has known that she is a writer, like her father, since she was 14, “when I read a short novel that described a scene that struck me: it was night, there was a boy at a train station, they put branches in a bonfire and, suddenly, the fire grew bigger. That wonderfully described scene seemed like magic to me. From that moment on, I wanted to be able to narrate like that.” It is a joy to see her smile, because one of her characters in The Greek Class, an Asian immigrant in Germany, asks “why in Europe do you have to smile when you see a stranger?”

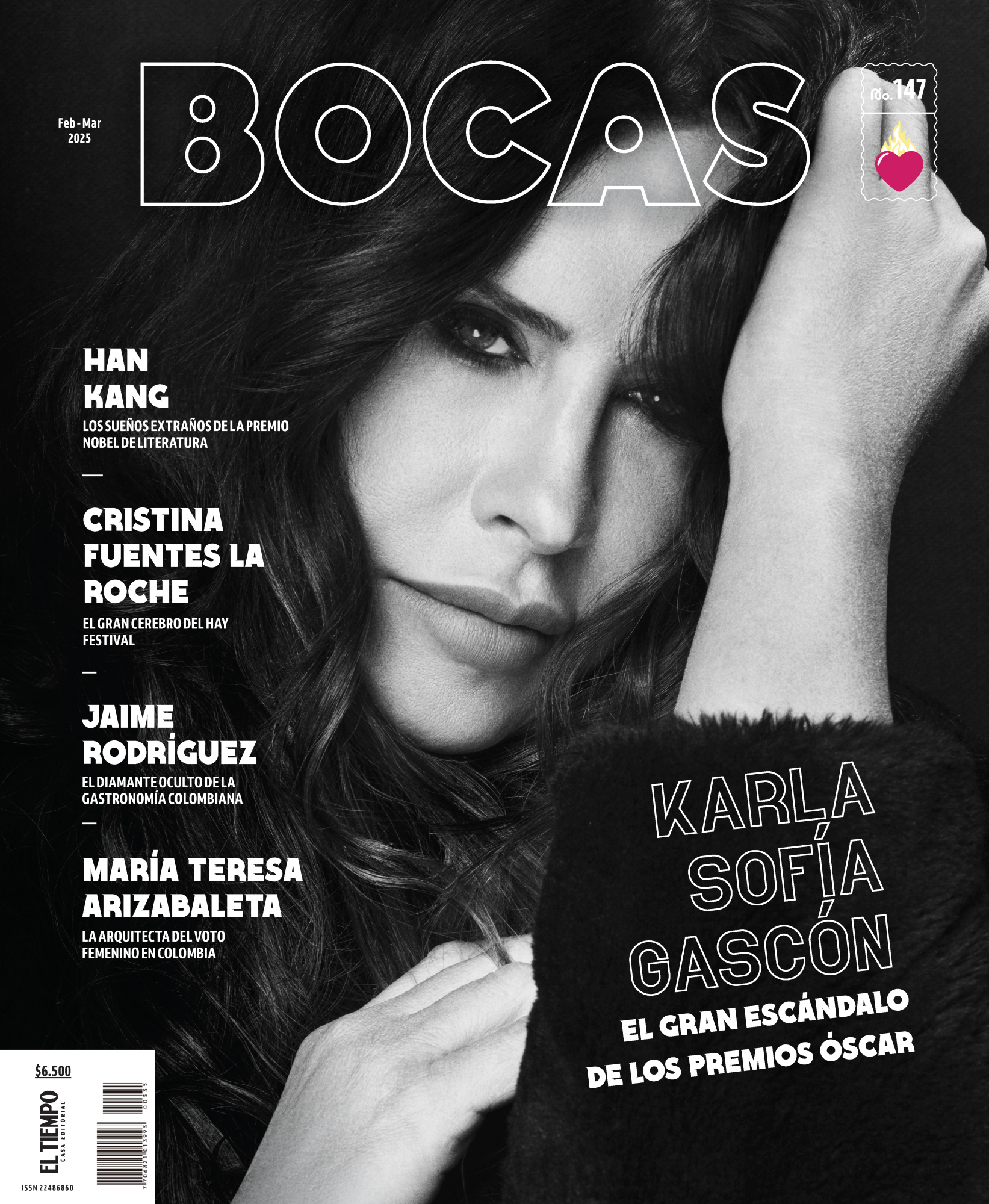

Han Kang, Nobel Prize winner in literature, is the new cover girl for BOCAS magazine. Photo: Getty

The author of The Vegetarian —a disturbing work about a woman who stops eating meat that turned her into an international cult writer— is characterized by the polyphony of narrators, the importance of the dreamlike, the allegories and the denunciation of the oppressions that crush the individual. But she slips some autobiographical elements into fiction: in Imposible decir adiós, her most recent work published in Spanish, which denounces a massacre committed by the Government of her country, one of the protagonists is dedicated to making videos, like the brother-in-law of 'the vegetarian', who is a video artist... and like Han herself. "Yes, I like to create in video," she comments. "I have recorded one of 18 minutes and 30 seconds with the same title as the novel, where I act together with another author friend of mine. We take a very large white cloth, that soft cloth that is used to wrap newborns, we are on Mount Hallasan, the highest in Korea, and we descend from there to the beach."

Your fiction writer in this last work is a bit antisocial, she is young but writes her will several times, she isolates herself from the world and lives in a way that makes her partners leave her, she has to rent a studio to work and, when she goes out, at night, she forces herself to behave like the rest of the world… Is that your vision of writers? “Well… I do have a private life, I drive a small car, I shop, I cook, I don’t spend all my time just writing. I graduated from university, I worked in a publishing house, then in a magazine, I was a university professor for 11 years, and now I have a bookstore in Seoul that I have run for seven years. It is true that, before, for a while, I left everything because I wanted to concentrate on writing a novel. But I have always maintained a relationship with society, with ups and downs, but generally quite intense. And I am still there. The author of the ending of Human Acts and who later stars in Imposible to Say Goodbye has a lot of me in her, but it is not 100 percent me. That character is a bridge that unites reality and fiction. Readers think that it is me as I am… and that creates misunderstandings. The nightmares, the dreams, the desires, the obsession with the massacre, the reflections on what life is, those things are mine.” She assures that, after receiving the Nobel Prize, “I have quickly returned to my normal life, to my routine, to being at home with my son. I don’t want pressure, I have many years of life left and I don’t want to stop writing or become stupid. With a prize like that you have some obligations, but I have cut them all and returned to my daily life. On January 1, 2025, I will start writing again. And I don’t need anything else.”

The moment Han Kang receives the Nobel Prize in Stockholm. Photo: Getty Images

I'm at home in Seoul. What you see looks like natural light coming in, but it's not. It's a very powerful white lamp. It's eight o'clock here at night. I've just had dinner with my son, with whom I live. Things are happening to me at this time: it's just when they called me from the Swedish Academy to tell me that I had won the prize.

Wonderful. He is a writer, he is in his eighties and he continues to publish novels.

What did he say to you when you won the Nobel Prize?

“I’m proud of you, daughter.” That’s what he said. The profession of novelist doesn’t pay much. When I was a child, we were poor and had to move often. We didn’t have much furniture, but we did have a lot of books. It was like being protected by books; to me they were like an expanding child because the number of them increased every week, every month. I went to five different primary schools, but I don’t remember feeling traumatized because I was protected by all those books I lived with. I spent, at each school change, the afternoons at home reading books until I managed to make new friends. So it’s a very precious memory.

You have five books translated into Spanish, but there are others in Korean that have not yet reached us. What are we missing from you?

They are missing my short novels. I would like them to be able to read them as well in time. I have also written poetry, which I hope will be translated one day.

Your most recent novel, Imposible to Say Goodbye, begins with a writer having nightmares about having written her last book, about a massacre carried out by her country's government. You seem to be doing the same with your previous novel, Actos humanos, about the Gwangju massacre in 1980.

That's right. The book about Gwangju appeared in May 2014, and I started having that recurring nightmare just a month later, in June. But the thing is, while I was writing Human Acts, I had had many other nightmares. I thought this one was just another one, an epilogue to those that came with contact with horror. However, the color and texture of this dream were different. That's why I wrote it down and thought it could be the beginning of a novel.

Can you describe that nightmare?

In my dream there were thousands of black trunks, so many trunks, on the side of a hill, so many that I couldn't count them, they were slightly tilted and had different heights, like people. They looked like graves to me. It was snowing. I was stepping in water, in puddles, suddenly I looked back and the horizon turned into the sea, which was overflowing, the water was starting to rise, I wanted to save the graves, with their bones, but I didn't even have a shovel, I started running and I woke up when the water reached my ankles.

In addition to The Vegetarian, in Spanish, other novels by him are also available, such as The Greek Class. Photo: Roberto Ricciuti / Getty

That is the beginning, literally, of Impossible to say goodbye.

Yes, my protagonist interprets it as a message and, together with his friend Inseon, he sets out to create an artistic work with 99 trunks that they have to plant. Nine is an incomplete number, it lacks something to get to another place.

It's amazing how his real dreams provide him with literary material. I imagine he must sleep with a notebook at his side.

No, no. I don't always have meaningful dreams. I have normal dreams, like everyone else. But sometimes I do realize that a dream has had a deep meaning. It seems like it's telling me something. Something important. Then, at that moment, because it's so shocking, it sticks in my mind, and I get up and have to write it down.

In Impossible to Say Goodbye, he deals with the massacre on Jeju Island in 1948, with 200,000 people killed by the political power. That same political power that, in 1980, massacred several thousand people in his hometown, ordering the army to shoot the people, the subject of Actos humanos. For the Colombian reader, these are little-known facts, but what about for the Korean one?

Many people know about the events in Gwangju. But not about the mass extermination on Jeju Island; that episode takes up just one line in our history textbooks. Many Koreans, by reading the novel, have really learned what happened. You in Colombia also had dictatorships and wars. In your country, as in Korea, there are still bodies to be found, with all those relatives who don't know where their dead grandparents are. I think you will connect with this theme of unhealed wounds. After a massacre, no matter where it happened, there are always people for whom it is impossible to say goodbye, to say goodbye to their loved ones. They continue to search for the bodies, the bones, of their family. Unfortunately, it is something universal, it happens all over the world. Gwangju is not a Korean city, it is synonymous with Auschwitz, Bosnia, Nanjing, the massacre of Native Americans...

In Colombia, you also had dictatorships and wars. In your country, as in Korea, there are still bodies to be found, with all those relatives who do not know where their dead grandparents are.

You, however, are not a political novelist at all.

No. My generation has no longer felt the need to dedicate its work to political commitment, but rather my aim is to investigate the interior of the human. But note that in The Vegetarian there is a woman who sheds her body with the intention of integrating into the plant kingdom, and in The Greek Class the protagonist has lost her speech because she rejects the violence of language and aspires to recover it through a dead language. These are gestures of rejection that attempt to recover dignity through a self-destructive action.

How did the Gwangju massacre affect you personally? You were 9 or 10 years old...

I was very young, and my family moved to Seoul just four months before the massacre, for other reasons, and we were able to escape unscathed because of that. My parents had a kind of survivor's guilt because of that. As a child, I heard a lot of stories about it, and one day I found a clandestine book at home, with some photos documenting the massacre, and in which there were atrocious images of mass murder and torture. I was in shock. It was horrible. I have always considered this subject very important, it deals with the essential questions about what it is to be human. My books are about that: the nature of the human, instinct. I wrote Human Acts to overcome the shock I was experiencing. I started researching the atrocity and I found all these dignified people, for example, those who did not shoot and let themselves be killed. I don't like the word victim, it means a certain defeat, but I don't think they were defeated, they just refused to be defeated. And that's why they were killed.

"My goal is to investigate the interior of the human." Photo: Roberto Ricciuti / Getty

What about Jeju Island?

The plot is that a woman in a Seoul hospital asks her friend to go to Jeju to feed her parrot so it doesn't die, and to do so she must go through a terrible snowstorm. As everything is born from a dream, the very texture of the narrative fuses time, history, memory and even the present. I always think that history is not just the past, but also the present.

In The Vegetarian, everything is realistic, although very surprising. But in these two novels based on real historical events, paradoxically, we see more fantastic elements, such as ghosts or the souls of the dead... It seems like 'magical realism'.

Ghosts and souls are very different things. I like to describe in a natural way those impossible scenes where the dead and the living meet, like, for example, Dong-ho, the boy who dies in Gwangju and who talks to the living, or looks at his own corpse in the street, and is evoked by many other characters. In the case of Impossible to Say Goodbye we don't know who is really dead and who is alive, but they converse, they are talking to each other, and logic tells us that this cannot be, that one of the two cannot be there. Snow is the basic element, it unites heaven and earth, the dead and the living, reality and fantasy. I move forward through these symbols.

BOCAS Magazine has two covers in this edition: Han Kang and Karla Sofia Gascon. Photo: Hernan Puentes / BOCAS Magazine

Your literature is very empathetic in the sensorial sense. I mean, readers get a pain in the bone in their hand when we see the scene of torture with the pen; we are terrified when the writer gets lost in the snowstorm; we are very impressed by the scene where the video artist films making love to the vegetarian... In other words, we remember from your book, obviously the plots, but many sensations and many images. I would like you to explain to me a little how that works, to provoke those intense sensations in someone who is reading a page that is nothing more than paper. I confess that, after the impact of some scene, I have had to put the novel down for a while and come back to it a little later.

When I write, I think about touch.

I think about how to describe touch, the physical sensation of being there; the sensorial is very important. When I write, I use my body. I use all the sensorial details of sight, hearing, smell, taste; I convey tenderness, warmth, cold, and pain. I have to notice that my heart is racing and that my body needs food and water, I walk and run, I feel the wind and rain on my skin. I try to infuse my sentences with those vivid sensations, to make it seem like the blood is coursing through my body. Writing is like sending an electric current to the reader. And when I feel that this current has been transmitted, I am amazed and moved.

In the case of Impossible to say goodbye...

I have to remember what sensations and feelings I had when I touched the snow. I have to feel it again. I was writing this novel for seven years, and since we have four seasons, it wasn't always winter, and that was a problem. So, for certain scenes I had to wait for winter to come back, and when it started to snow, I would go out into the street to feel the snow. It didn't matter what I was doing, eating, working, meeting... if it snowed, I would stop everything and go out to feel the snow. And then I would go to the forest, I would call a taxi to take me to the mountain near my house, and there I would start to step on the snow to feel what it was like to walk on it; I would touch the snow that accumulated on the branches of the trees, I would see how it melted, how long it took, how it melted, all this for hours, days, weeks... And I also felt that each snowflake had its weight and that the humidity of the snow is also different.

In The Vegetarian there is a woman who sheds her body with the intention of integrating into the plant kingdom, and in The Greek Class, the protagonist has lost her speech because she rejects the violence of language and aspires to recover it through a dead language.

But whatever happens, it will happen.

Yes. It was all the same to me, if I was having tea with my friend, it was bad luck; if it suddenly snowed, I went outside. It was my fieldwork for the novel. To the point where I could no longer enjoy the snowfall in peace, looking at it from the window. When I published the book in the autumn of 2021, I look back with great pleasure on that winter of 2021 because I could finally relax at home looking at the snow like everyone else. My friends, who are very patient, call me on the phone when it snows: “I remember you, Kang.” That snow has produced a whole book.

Of course, you make snow into a threatening monster, an explosion of purity, a narcotic…

It's funny what you said earlier that you have to put the book down for a while. Because when I write, I can't sit still for long either. I write for about 30 or 40 minutes and then I can't go on, my concentration is gone. Then I get up, walk for another 30 or 40 minutes or do some housework and then go back to writing. I write short and several times, in bursts.

Among the scenes that stick in your memory, there is one that has nothing to do with violence or sensuality, but is very symbolic: in Actos humanos, a company of actors has their play censored and they perform it anyway, but moving their lips on stage, without saying the words. How did you come up with that?

That's what happened! The actors began to act without saying anything, only letting out a few moans. During the dictatorship, all books, scripts and librettos had to be previously reviewed by a censor. There was one company that found the entire play crossed out; they couldn't say a single sentence. So they came up with the idea that, without breaking the law, they could perform it without words. It was something that was branded in my heart, which is why I included it in my novel, although the details of the story and the play have nothing to do with the real ones.

Your characters are either sick, with migraines like you are suffering from, or more serious illnesses, or they are injured or bleeding or have mental health problems. It is as if it were impossible to be healthy in this world. There are many hospitals, health centres… What are you telling us? Because sometimes it seems that the asylum is outside the walls of these centres, rather on the street.

I believe that human beings, all of us, are born very weak. And the same thing happens when we die, we are very weak. In between, let's not fool ourselves, we never get rid of that constitutive weakness; all human beings retain that weak side, more or less buried or manifest. And I think that literature has to deal with this subject, the fragility of the human being. My characters relate to each other through their pain, their fragility, which is what connects them. By feeling that pain you relate to others. I believe that this is one of the evidences of love, that is, suffering opens you up to the other. It is as if I had suddenly found the meaning of love, and my novels are love stories.

I have quickly returned to my normal life, to my routine, to being at home with my son. I don't want pressure, I have many years left to live and I don't want to stop writing or become stupid. With a prize like that, you have some obligations, but I have cut them all.

Especially The Greek Class, which can be seen as a romance between a mute woman and a blind man...

They all talk about love, because they talk about pain. To love means to include, to embrace the suffering of another, that you care about, love makes you empathetic. We suffer, our body suffers, our mind suffers, but through this process we maintain a relationship with others and, in the end, we love. I think that is what it means to have a relationship. For example, the scene where Inseon cuts off his fingers while working in the workshop.

The tips of his fingers that have fallen to the ground are collected and reattached in the operating room. To make them active again, forming part of the whole, they have to be pricked every three minutes, inflicting pain, so that the finger is well-groomed. This is pure medicine and shows that through suffering we relate and unite.

All of this is achieved by interweaving the characters with nature, without reaching the extreme ideal of the girl in The Vegetarian, who starts from a verse by the poet Yi Sang: 'I think that humans should be plants'.

In Imposible decir adiós I focus on the cycle of water, which evaporates, rises vertically to the sky and then moves horizontally as well, through the wind and the sea. Through these lines we can know that the earth is united. We are all connected and related. I always think about that when I write, about how we can establish links. Literature unites people who live in different places, in different historical periods, but who are reading the same book.

Just one question about the political situation in Korea and the self-coup last December.

Everything is constantly changing, very quickly. I still have hope that things will improve. On the day martial law was declared, on December 3, there were citizens blocking the passage of tanks with their bodies. Many people mobilized to prevent a repeat of the past. Watching these scenes, I was very moved and I had hope that everything will be fine. Right now, I cannot say that the situation is good, but rather quite complex, but I still believe that it will be resolved.

Han Kang with the Nobel Prize in his hands. Photo: Getty Images

His most distinctive book of all is Blanco, a kind of dictionary of terms related to that color…

At first I just thought, 'I'm going to write about white things.' And then I remembered my older sister, who died two hours after I was born. Without her death, my parents would certainly not have decided to have me. In the first part, white things appear from my point of view. In the second, I lend my body to my dead sister, so that she can tell me the white things she sees. But my older sister and I cannot coexist, because if one is there, the other cannot be there, so in the third part, we have the farewell ceremony. That's the book.

In the cruelest or most savage scenes, you are able to find beauty or noble acts. Can you explain this beauty that exists even in the most horrible things?

There are two sides to us, a dark side and a light side. We are capable of horrible cruelty and the greatest generosity. I show both, but I always walk toward the light, because I am alive. This is not because I want to, a decision I have made, but a force that draws me toward that bright path. That is my theme: the broad spectrum of humanity, from the sublime to the brutal, the whole spectrum. When I read brutal documents about Gwangju for three months, my faith in humanity crumbled. I felt frustrated, unable to continue writing, and was on the verge of giving up. But I found the diary of a member of the civil militia who, before he died, wrote: “Oh God, why does this thing called conscience pierce me and hurt me so much? I want to live!” I saw that this was the way: to move toward human dignity. In my future works I will continue to explore that path. As much as I deal with the dark, the suffering, I always—both in my life and in my novels—go toward the light.

Have you had any dreams lately?

Yes. I often dream that I am in nature, in the forest and then inside a beautiful glacier, surrounded by trees. It is a very pleasant dream.

BOCAS MAGAZINE, EDITION 147

Recommended:

Alessandro Baricco Photo: Ricardo Pinzón / BOCAS Magazine

eltiempo